THIRTEEN SOLDIERS WHO FAILED TO RECEIVE

MEDALS OF

HONOR

UNDER THE ARMY’S “KILLED/NO MEDAL” POLICY

Michael C. Eberhardt (2023)

INTRODUCTION

(T)he medal of honor cannot be awarded in

the case of a deceased soldier, no

matter what measure of gallantry he may have displayed.

Very respectfully,

The Adjutant

General

Over a century later, it now sounds almost

inconceivable but this early 1900s statement[1]

reflected the then Army interpretation of the 1862 Act that authorized the

Medal of Honor; this interpretation precluded the issuance of a Medal of

Honor to a soldier who did not survive the action which demonstrated his

gallantry, or who was otherwise deceased when his Medal of Honor was

approved. In his exceptional 2018

book, The Medal of Honor, The Evolution of America’s Highest

Decoration, historian Dwight Mears chronicles this interpretation which

was eventually reversed at the direction of the Secretary of War in 1918.

In 1895 the Army … formalized a curious interpretation of the Medal

of Honor statutes,

requiring soldiers to survive their acts of valor to receive the

decoration…. In 1895 the

Army judge advocate general ruled that the original Medal of Honor

Statutes of 1862 and

1863 were “manifestly intended to honor and distinguish the recipient

in person.”

Therefore, absent “special authority of Congress” he determined that

a Medal of Honor

“could not legally be awarded to the widow, or a member of the

family, of a deceased officer,

on account of distinguished service in action performed by the latter

in his lifetime.”[2]

Further insight into the rationale behind the 1895

ruling, and the basis for the likely application of this policy informally

in the decades prior to 1895, is found in an earlier 1891 opinion of then

Acting Army Judge Advocate General Guido Lieber who noted in a memorandum as

follows:

The question upon which an opinion is desired is whether the War

Department has authority

to issue a medal of honor to the relatives for a deceased soldier.

….

Without the examination of any law on the subject, I should say that

a medal of honor is a

thing pre-eminently of a personal character, intended to honor the

person upon whom it is

conferred, and that when such person dies it becomes impossible from

the very nature of

things any longer to confer such honor upon him, and that there can

be no such thing as

conferring the honor on the dead though the living.

….

Medals of Honor additional to those authorized by the act

(Resolution) of July 12,

1862, and present the same to such officers, non-commissioned

officers and privates as have

most distinguished or who may hereafter most distinguished themselves

in action….

The words “Present the same to such officers, etc.,” leave no doubt

as to what was

intended.[3]

The ability to physically present a Medal of

Honor to a living person was therefore the guiding principle underlying the

original Army interpretation of the 1862 Act.

This “Killed/No Medal” policy was finally reversed at

the direction of the Secretary of War in early 1918, and an ensuing February

15, 1918 directive from the Adjutant General of the Army to the Judge

Advocate General reads in part:

The Secretary of War directs you submit to this office a draft of

a bill providing in effect

that the Medal of Honor may be awarded posthumously to persons killed

in the performance

of acts meriting such award, or to persons whose death from any cause

may have occurred

prior to such award….

The directive from the Secretary of War to the Adjutant

General also stated that the existing general order relating to Medals of

Honor be amended to state:

The medal so awarded shall be issued to the nearest heir of

the deceased person.”[4]

(Emphasis added by author.)

While a bill was drafted for the Secretary of War,

formal legislation was not required and the Army acted thereafter in

accordance with the Secretary of War’s direction. Interestingly, in the

immediate aftermath of the Army’s 1918 reversal of policy, over 20 soldiers

were issued the Medal of Honor posthumously for actions during WWI.

Dwight Mears further characterizes the 1895 Judge

Advocate General ruling and the 1918 reversal as follows:

(T)he Army’s 1862 law directed that Medals of Honor “be presented, in

the name

of Congress, to such non-commissioned officers and privates.” The

judge advocate general

evidently construed this clause to preclude the awarding of a medal

to anyone other than the

service member, given the omission of explicit authorization to

present the medal

posthumously or to a deceased soldier’s next of kin. There was no

clear intent to deny the

medal to deceased soldiers, either in the law’s text or in its

legislative history…. This

interpretation was never legislatively or judicially overruled, but

the Army (in 1918)

eventually

revoked this rule as a matter of internal policy. Officials likely realized

that

qualifying

actions resulting in death were often more gallant than those in which the

soldiers

survived,

particularly when they sacrificed their own lives for altruistic reasons.[5]

(This author found no indication that the Navy adopted

a similar “Killed/No Medal” interpretation of the separate 1861 Act that

authorized Medals of Honor specifically for members of the Navy.)

The identity of every Army soldier whose death from

1862 to 1918 may have disqualified him from a Medal of Honor can likely

never be known. There are

however multiple examples in Army records of some deceased soldiers whose

names surfaced as potential Medal recipients only to have the Army policy

invoked, thereby halting any formal recommendation and review process.

However, while there are examples of a number of

soldiers who never had their recommendations formally considered because of

the Army “Killed/No Medal” policy, there are --- as this article

identifies---clear and definitive official documents that prove:

·

Eight soldiers were formally approved for

Medals of Honor, but the Medals were not issued because they were killed or

did not survive the award date.

·

Another three soldiers failed to receive

Medals of Honor where the written recommendations by their Commanding

General (himself a Medal of Honor recipient) were not acted upon because of

the Army policy.

·

And, remarkably, there are two soldiers who

never received their approved Medals of Honor because the Army may have

thought they were dead or unaccounted for, but in fact one survived until

1930 and the other to 1963.

This article examines those thirteen cases and poses

the obvious question regarding an appropriate remedy.

ARMY “POLICY” VERSUS PRACTICE

While, as noted above, the documentation cited herein

makes clear that Medals of Honor were not issued despite approval to

specific Army soldiers who were killed, there is also additional

documentation which demonstrates an inconsistent application of the

“Killed/No Medal “policy during the period 1863 to 1902. As a result, at

least 40 deceased soldiers were in fact awarded Medals of Honor during that

period even though they died prior to award.

See the list at Appendix 1.

These awards and issuance of Medals for deceased soldiers, despite

the policy to the contrary, may be partially explained by the absence of any

written opinion regarding the policy until the 1895 Army judge advocate

general opinion. Indeed, the Army’s first formal regulation on the standards

for issuance of the Medal did not occur until 1897.

Accordingly, it seems plausible that not everyone in the Army during

the Civil War (in the immediate aftermath of the enactment of the 1862

statute), or during the succeeding widespread actions of the Indian War

period through the 1880s, may have known that there was a Medal of Honor

policy regarding killed soldiers, or even subscribed to it if there was any

awareness.

Furthermore, relevant to the later discussion in this

article of deceased soldiers who failed to receive Medals of Honor that were

approved for actions during the Philippine Insurrection, it is noted that

there were four soldiers who were killed during that war who not only

received Medals of Honor, but whose prior deaths were explicitly recognized

in the General Order recording the Medals. See

Appendix 1.

These inconsistencies only add to the contention that a

remedy is certainly due the thirteen soldiers identified in this article.

SERGEANT STEPHEN FULLER AND PRIVATE THOMAS COLLINS

THE BATTLE OF CHIRICAHUA PASS

On October 16, 1869, under the command of Captain

Reuben Bernard, 60 men assigned to “G” Troop, 1st Cavalry and “G”

Troop 8th Cavalry out of Fort Bowie, Arizona began tracking

Cochise and a band of 100 Apache warriors who had for months been raiding

extensively in the Dragoon and Chiricahua mountains of Arizona.

These soldiers included Sergeant Thomas Fuller and Private Thomas

Collins. Four days later, on

October 20, 1869, deep in the Chiricahua Mountains, after a five-hour

intense battle with Cochise and his warriors, Sergeant Fuller and Private

Collins lay dead---both shot in the head as they and about 30 other soldiers

were directed by Captain Bernard to charge an Apache position up a rocky

mesa where the Apaches were able to fire down at the soldiers from a

superior position. When the

firing stopped and Captain Bernard ordered a retreat, only Sergeant Fuller

and Private Collins had been killed, while two other enlisted men had been

injured. Private Edwin Elwood had been shot in the cheek and Private Charles

Ward had fallen and broken his leg.

At the time of his death, Sergeant Fuller was 35 years

old and on his third enlistment after coming to the U.S. from Ireland in

1856. He became a naturalized U.S. citizen in 1866. Like Sergeant Fuller,

Private Collins came to this country from Ireland; he was 30 years old when

he was killed. Private Collins,

having enlisted at Fort Bowie less than 30 days prior to his death, was

likely in his first real field engagement with the Apaches on October 20,

1869 when he was killed.

Following Captain Bernard’s orders that the soldiers

retreat from the rocky mesa, he perceived a continuing danger from the

Apaches in attempting to retrieve the bodies of Sergeant Fuller and Private

Collins. The bodies of these two Irish immigrants were therefore left behind

on the rocks where they fell, but retrieved three days later and buried near

the battle site. (Their likely unmarked graves have only recently been

identified.)

Rocky

mesa where Sgt Fuller and Pvt Collins were killed

Possible Graves of Sgt Fuller and Pvt Collins

Captain Bernard wrote a detailed after-action report on

October 22, 1869 describing the gallantry of the 31 soldiers who had charged

the rocky mesa and their assault on the superior position of Cochise and his

warriors, and he used that report as the basis for a written Medal of Honor

recommendation in December 1869 in which all the listed 31 soldiers,

including specifically Sergeant Fuller and Private Collins.

In his own handwriting, Captain

Bernard’s recommendation to Colonel John P. Sherburne, Assistant Adjutant

General, reads in pertinent part:

I have the honor to submit the following names of the Men of the

Troops G 1st and 8th

Cavalry for gallantry displayed during the engagement on October 20th

in the Chiricahua

Mountains. These men are

they who advanced with me up the steep and rocky mesa under as

heavy a fire as I ever saw delivered from the number of men

(Indians), say from one hundred

to two hundred.

These Men advanced under this fire until within thirty steps from the

Indians when they came

to a ledge of rocks where every man who showed his head was shot at

by several Indians at

once; here the men remained and did good shooting through the

crevices of the rocks until

ordered to fall back, which was done by running from rock to rock

where they would halt and

return the fire of the Indians.

When a Government gives an incentive to men for special good conduct,

I feel confident in

saying that every one of these men is justifiably entitled to be

specially rewarded.

(Emphasis added by author.)

[6]

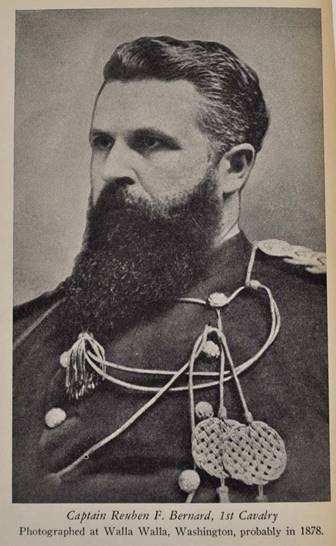

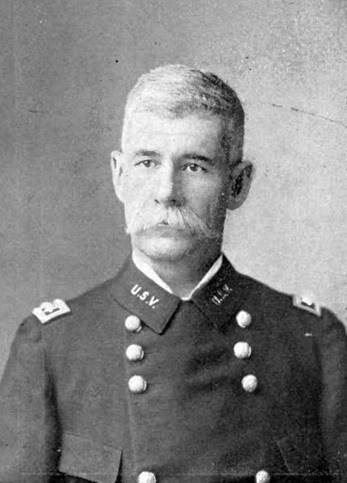

Captain

Reuben Bernard

Captain Bernard’s December 1869 recommendation found

its way swiftly through the Army approval process. In a January 31, 1870

document[7]

there are handwritten entries evidencing the concurrences from Major General

Edward Ord, Commanding General of the Department of California and Adjutant

General Edward Townsend. Most

importantly, the document contains the handwritten concurrence by the Army’s

final Medal of Honor authority at the time, General William Sherman,

Commanding General of the Army.

The document containing these approvals and concurrences refers to the 31

soldiers recommended by Captain Bernard.

Remarkably though, as engraving orders for the Medals of Honor were

thereafter being prepared for issuance to each of the 31 soldiers on the

approved list, someone entered a notation next to the names of Sergeant

Fuller and Private Collins---“KILLED NO

MEDAL.”[8]

The remaining 29 soldiers who had survived the Battle of Chiricahua Pass

received their Medals of Honor shortly thereafter.

The wounded soldiers, Private Elwood and Private Ward, were two of

these recipients.

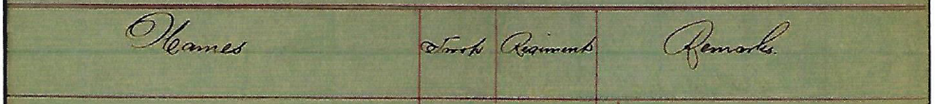

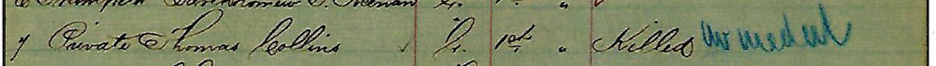

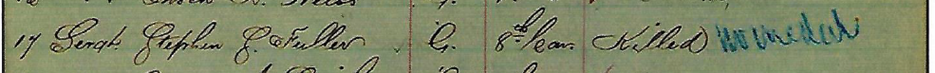

Excerpt of approval document

where “Killed No Medal” entry made next to names of Sgt Collins and Pvt

Fuller

The document evidencing General Sherman’s concurrence

and the notations next to the names of Sergeant Fuller and Private Collins

lay unappreciated in the National Archives until 2019. Thereafter, in

November 2020, following a detailed published article[9]

on the Battle and the Medal of Honor documentation, this author ---with the

substantial aid of two retired Army Major Generals (one of whom is a Medal

of Honor recipient) --- provided all of the relevant documents to the Army

to seek a correction of the records to indicate that Sergeant Fuller and

Private Collins were in fact both approved for the Medal of Honor. Despite

the provision of those documents, and in the wake of a series of uninformed

initial responses by the Army, there has been no Army action in over two

years; Sergeant Fuller and Private Collins remain victims to the Army’s

seriously flawed interpretation of the 1862 Act and their remains are left

behind deep in the Chiricahua Mountains.

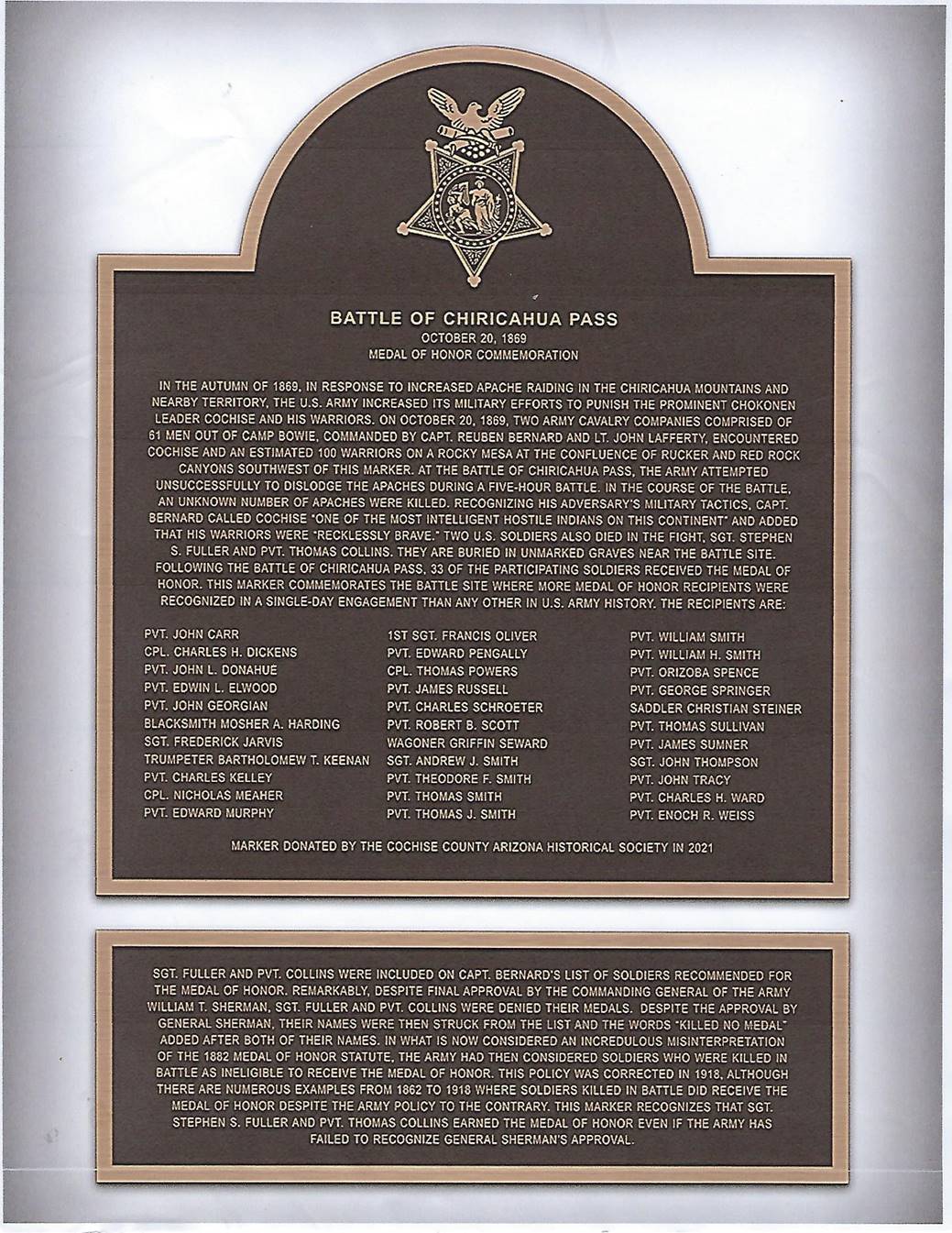

This author, with the cooperation of the Cochise County

Arizona Historical Society, has recognized Sergeant Fuller and Private

Collins on a marker placed in February 2022 near the battle site; their

companion soldiers who received Medals of Honor are also listed.

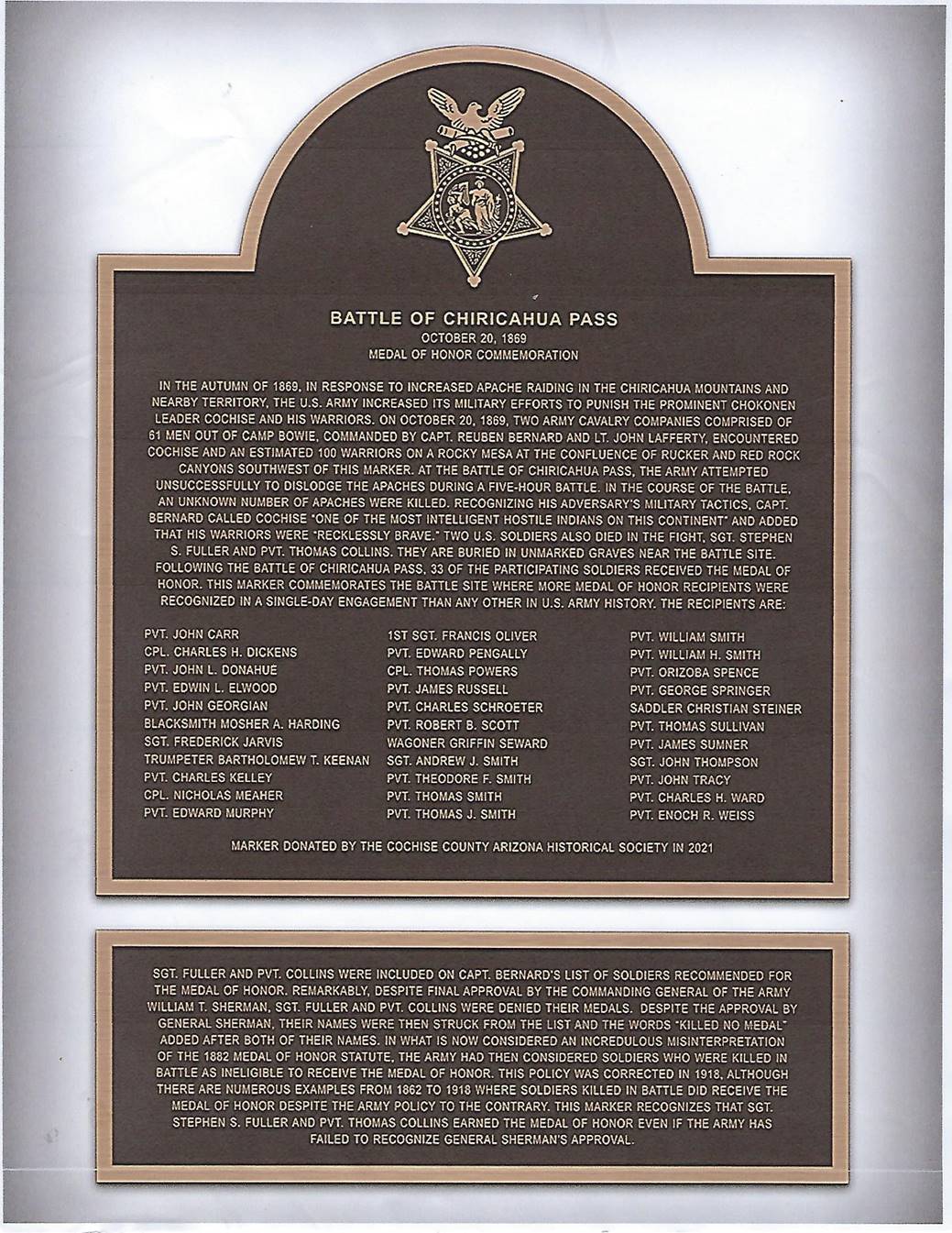

Marker commemorating Battle

with recognition of Sgt Fuller and Pvt Collins

PRIVATE

JAMES HARRINGTON AND TEN OTHER SOLDIERS

THE

BATTLE OF SAN MIGUEL AND THE BATTLE OF SAN ISIDIRO

THE

PHILIPPINES ISLANDS 1899

Yet another Irish soldier, Private James Harrington, was

denied the Medal of Honor because he was killed in battle in the Philippines in

1899. However, like the 29

survivors who received Medals of Honor for their gallantry in the 1869

Battle of Chiricahua Pass, 13 of the surviving scouts in Private

Harrington’s troop in the Philippines in May 1899 also received Medals of Honor.

However, Private Harrington and ten other Army soldiers in the Philippines were

denied Medals of Honor under circumstances as compelling as those affecting the

denials to Sergeant Fuller and Private Collins thirty years prior.

Private Harrington, born in 1853 to Irish immigrants,

served as part of a small elite group of scouts known as “Young’s Scouts” during

the Army’s engagement in the “Philippine Insurrection” (also referred to as the

Philippine-American War) from 1899 to 1902; this Insurrection followed the

United States assumption of control over the Philippines after the defeat of

Spain in the Spanish American War.

William Young was a civilian volunteer scout in the Philippines who had served

previously in the Army in the Nez Perce War.

The formation of “Youngs Scouts” was conceived by General

Henry W. Lawton, himself a Civil War Medal of Honor recipient, and who was

commanding the Northern campaign in the Philippines in 1899.

General Lawton observed Young in action one day as a volunteer soldier

and was immediately impressed by his bravery and leadership. Thereafter, Young’s

Scouts served as an advance guard for especially dangerous assignments in

engagements with the Philippine insurrectionists.

It was comprised of men specifically

hand-picked from the 1st North Dakota Volunteers, the 2nd

Oregon Volunteers and the 4th U.S. Cavalry. Private Harrington was

one of the soldiers from the 2nd Oregon Volunteers. This elite group of scouts

varied in size from 12 to 25 during its existence during 1899.

In May 1899, under the command of Captain William

Birkheimer (who himself was awarded the Medal of Honor for his action in the

Philippines), a number of Young’s Scouts were involved in two dangerous and

intense assault actions. They were

led by Young and Private Harrington. These actions are referred to as the Battle

of San Miguel on May 13 and the Battle at Tarbon Bridge near San Isidiro on May

16 (hereinafter the Battle of San Isidiro).

In each case, the actions involved strategically important positions and

the scouts were significantly outnumbered.

At the Battle of San Miguel on May 13, a reconnaissance

party of 11 scouts commanded by Captain Birkheimer was confronted by 200-300

insurgents and lead by Young, who was mortally wounded, and Private Harrington.

The insurgents were routed. For

their actions, Captain Birkheimer and 11 scouts, including Private Harrington

were recommended by General Lawton for Medals of Honor in his report filed on

September 26, 1899 and addressed to the Adjutant General of the United States.

In describing the action at San Miguel on May 13, 1899,

General Lawton’s report to the Adjutant General reads:

…. brought the support forward promptly in extended order, but before it

could

come up and engage, 12 scouts on the left of the center, encouraged by

two of their number

(Chief Scout young and Private Harrington), under the direct supervision

of Captain

Birkheimer, broke from the bushes which temporarily concealed them and

charged straight

across the open for the right center of the enemy’s line, which wavered,

broke, and, carrying

with it the flanks, precipately fled before the scouts could reach it.[10]

Three days later, a slightly larger group of scouts, again

including Private Harrington, discovered that some 600 Philippine insurgents had

entrenched themselves near the strategically placed Tarbon bridge over the river

one mile from San Isidiro and were intent on burning it.

The scouts rushed the bridge and prevented the burning, and subsequently

drove the insurgents from their trenches with the aid of the Second Oregon

Volunteers, thus recapturing control of the bridge. The only soldier killed at

the battle at the bridge near San Isidiro on May 16, 1899 was Private

Harrington. Ominously, only the day

before Private Harrington had remarked to his fellow scouts that the bullet had

not yet been made that could kill him. When General Lawton arrived with a troop

of mounted cavalry to begin repairs on the bridge, he was told of Private

Harrington’s death and he directed that an American flag be placed over his

body.

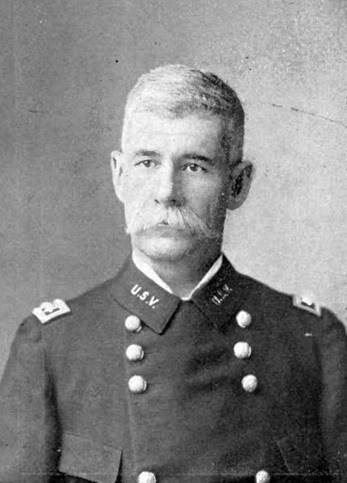

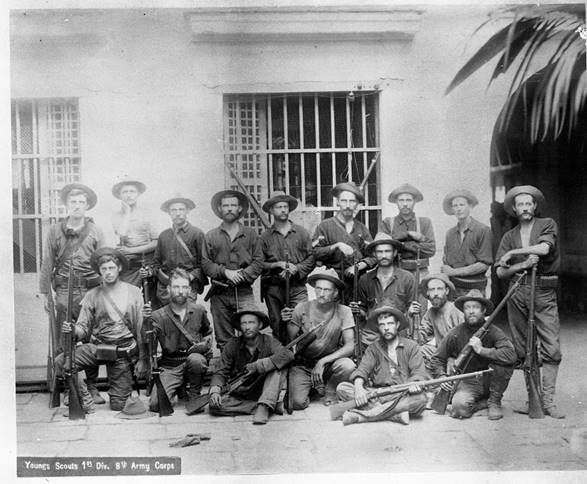

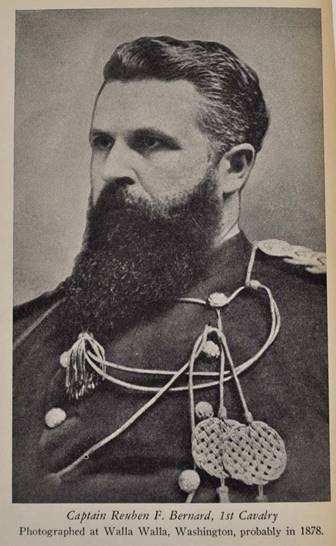

Major General Henry W. Lawton

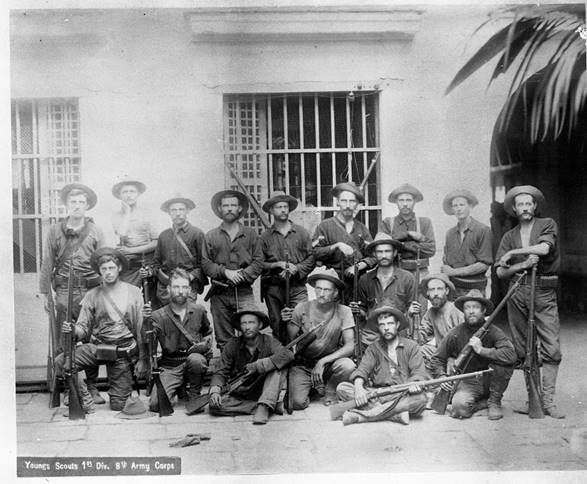

Young’s Scouts

In his report to the Adjutant General in September 1899,

General Lawton describes Private Harrington’s death:

Harrington, killed, the only casualty, is the man who has several times

before been

commended for unusual bravery. He was as noble and brave a soldier as I

have ever known,

and his death…. will be great loss to us.[11]

In the same September 1899 report to the Adjutant General,

at page 92, General Lawton included the list of the following 11 soldiers, as

well as Captain Birkheimer, from the Battle of San Miguel in his recommendation

for Medals of Honor:

Private Eli L. Watkins, Troop C, Fourth U.S. Cavalry

Private Simon Harris, Troop G, Fourth U.S. Cavalry

Private Peter H. Quinn (also McQuinn), Troop L. Fourth U.S.

Cavalry

Corporal Frank L. Anders, Company B, First North Dakota

Volunteer Infantry

Private J. W. McIntyre, Company B, First North Dakota

Volunteer Infantry

Private Gotfried Jensen, Company D, First North Dakota

Volunteer Infantry

Private Willis H. Downs, Company H, First North Dakota

Volunteer Infantry

Private Patrick Hussey, Company K, First North Dakota

Volunteer Infantry

Private Frank W. Summerfield, Company K, First North Dakota

Volunteer Infantry

Private Edward Eugene Lyon, Company K, Second Oregon

Volunteer Infantry

Private James Harrington, Company G, Second Oregon

Volunteer Infantry

General Lawton’s report to the Adjutant General, at page

96, also recommended the following 22 men for Medals of Honor for the action at

the Tarbon bridge near San Isidiro on May 16:

Private Peter H. Quinn

(also McQuinn), Troop L. Fourth U.S. Cavalry

Private Simon Harris, Troop G. Fourth U.S. Cavalry

Private Edward Eugene Lyon, Company B, Second Oregon

Volunteer Infantry

Private Marcus W. Robertson, Company B, Second Oregon

Volunteer Infantry

Private Frank Charles High, Company G, Second Oregon

Volunteer Infantry

Private M. Glassley, Company A, First North Dakota

Volunteer Infantry

Private Richard M. Longfellow, Company A, First North

Dakota Infantry

Private J.W. McIntyre, Company B. First North Dakota

Volunteer Infantry

Private John B. Kinne, Company B, First North Dakota

Volunteer Infantry

Private Eli L. Watkins, Company C, First North Dakota

Volunteer Infantry

Private Gotfried Jensen, Company D, First North Dakota

Volunteer Infantry

Private Charles P. Davis, Company H, First North Dakota

Volunteer Infantry

Private S.A. Galt, Company G, First North Dakota Volunteer

Infantry

Private W.H. Downs, Company H, First North Dakota Volunteer

Infantry

Private J. Killion, Company H, First North Dakota Volunteer

Infantry

Private Frank Fulton Ross, Company H, First North Dakota

Volunteer Infantry

Private Otto Boehler, Company I, First North Dakota

Volunteer Infantry

Private John F. Desmond, Company I, First North Dakota

Volunteer Infantry

Corporal W.F. Thomas, Company K, First North Dakota

Volunteer Infantry

Private F. W. Summerfield, Company K, First North Dakota

Volunteer Infantry

Private Patrick Hussey, Company K, First North Dakota

Volunteer Infantry

Private T.M Sweeney, Company K, First North Dakota

Volunteer Infantry

(Note: Several of the listed soldiers appeared on

both of General Lawton’s lists. However, of those who did receive their Medals

of Honor, none were issued two Medals.)

In total, in addition to Captain Birkheimer, thirteen of

the men on the two foregoing lists eventually received Medals of Honor as a

result of War Department approvals in 1906. They

were:

Private Peter H. Quinn

Corporal Frank L. Anders

Private Gottfried Jensen

Private Willis Downs

Private Edward Eugene Lyon

Private Marcus W. Robertson

Private Frank Charles High

Private Richard M. Longfellow

Private John B. Kinne

Private Charles P. Davis

Private S.A. Galt

Private Frank Fulton Ross

Private Otto Boehler

However, another eleven soldiers on General Lawton’s two

lists from 1899 never received Medals of Honor. So, what happened to these

soldiers? As detailed below, eight of the eleven were specifically listed on two

1906 War Department Medal of Honor approval lists but never received Medals. And

the other three soldiers can also be similarly accounted for as non-recipients

because of the same “Killed/No Medal’ policy then in effect.

The January 8, 1906 War Department approval list.

This document, signed by the Assistant Secretary of War, contains a list of ten

soldiers as approved Medal of Honor recipients for the Battle of San Miguel.

Five soldiers received their Medals but five soldiers did not, including Private

Eli L. Watkins, Private Simon Harris, Private James W. McIntyre, Private Patrick

Hussey and Private Frank Summerfield.

These are five of the eight soldiers where no Medal of Honor was issued

despite being on the War Department approved list. The January 8, 1906 list

includes language that reads in part:

By direction of the President, let a medal of honor be awarded to each of

the following

named men, if living, for most distinguished gallantry in action

at San Miguel, Luzon,

Philippines on May 13, 1899. (Emphasis added by author)[12]

An accompanying War Department document of January 8, 1906,

signed by the War Department’s Military Secretary, also refers to the approved

soldiers, as well as Private James Harrington’s circumstance, and reads in

pertinent part:

It is further shown by the records that each of these men was

specifically mentioned for

distinguished gallantry in the charge of May 13, 1899, and that Captain

Birkheimer and

Major General Lawton recommended, in terms almost identical with those

employed in the

case of E.E. Lyon, and set forth hereinbefore, that each of these men

(except Harrington, who

died shortly thereafter) be awarded the Congressional medal of honor for

distinguished

gallantry on that occasion.[13]

The April 4, 1906 War Department approval list.

In a second War Department document dated April 4, 1906, relating to the Battle

of San Isidiro and signed by the Assistant Secretary of War, is a list that

includes the names of ten more soldiers approved for the Medal of Honor, but

three of these soldiers never had Medals of Honor issued to them.

These three soldiers are: Private Michael Glassley, Private John Desmond,

and Private William Thomas. In

pertinent part, the April 4, 1906 San Isidiro list includes language which

reads:

By direction of the President, let a medal of honor be awarded to each of

the following men,

if living, for distinguished gallantry in action near San Isidiro,

Philippine Islands[14]

(Emphasis added by author)

THE PLIGHT OF ELEVEN PHILIPPINE SOLDIERS

The historical documents do not fully explain why it took

over six years for the War Department to issue the two Medal of Honor approval

lists in 1906 for the 1899 battles at San Miguel and San Isidiro.

General Lawton was killed in action in December 1899 after publishing his

recommended lists for each battle in his official report of September 1899.

While his death might have slowed the review process, there is evidence

however that an initial board of officers was convened in 1900 and recommended

the issuance of Medals of Honor for the 1899 battles.

However, the records are not clear as to

any immediately ensuing review actions within the Army.

Not until a letter from former Private Edward Lyon in

December 1905 did the recommendations for the Medals get further attention by

the War Department. Unquestionably,

this six-year gap in approval action worked to the detriment of several soldiers

who were on the approved 1906 War Department lists but who were either dead by

the time of those 1906 approvals or unaccounted for.

Consider the summary of facts regarding the following eleven soldiers ---

eight of whom served with the First North Dakota Volunteer Infantry (whose names

are marked with an asterisk):

1.

Private F.W. Summerfield* (who

appeared on both of General Lawton’s lists) was killed in action in Calabarzon

in the Philippines on January 20, 1900.

Why the War Department did not know of his death when it approved Private

Summerfield’s Medal of Honor in 1906 is a curious oversight.

In January 1906, Private Summerfield’s parents learned of their son’s

name on the War

Department approved list for the battle of San Miguel.

They made a request for their

son’s Medal of Honor to the War Department through Senator Porter

McCumber of

North Dakota. Their request

was denied in a War Department letter indicating there was

no authority to issue a Medal of Honor for a deceased soldier.

Private Summerfield is

buried in Lisbon, N.D.

The War Department response to the parents of Summerfield’s parents is

inexplicable

when compared to a similar situation only four years prior when Mary

Leahy, the mother

of Private Cornelius Leahy, corresponded with the War Department and

requested

her deceased son’s Medal of Honor. Private Leahy, born in Ireland in

1872, was assigned

to Company A, 36th U.S. Volunteers, and was recognized for

gallantry during action on

September 3, 1899 near Porac, Luzon, in the Philippines.

His Medal of Honor award

date was May 3, 1902 but he had been killed in action prior to that on

December 1, 1900

in Luzon. On May 9,

1902, Private Leahy’s mother received his Medal.

Private Leahy

is one of the four soldiers from the Philippine Insurrection who was

killed but

nonetheless received the Medal of Honor.

The War Department actions

that lead to the award of these four Medals are noteworthy not only

because they were

exceptions to the then War Department policy, but these awards were

processed within a

timeframe far less than the six plus years needed to process the belated

approvals for the

battle participants at San Miguel and San Isidiro.

2.

Private Eli L. Watkins (who appeared

on both of General Lawton’s lists) was killed in Philippines on July 20, 1901.

He is buried in Clark Veterans Cemetery, Central Luzon, Philippines.

Curiously, there is 1906 War Department correspondence to another Medal

recipient asking for any information about the whereabouts of Private Watkins.

As was the case with Private Summerfield, why the War Department did not know of

Private Watkins’ death when it included his name on its 1906 approved list is

perplexing.

3.

Private John Desmond* died in San

Francisco on July 31,1900 after his discharge.

In 1906, a War Department letter notifying Private Desmond of his

award was sent to an outdated address in Wahpeton, N.D. and returned.

He is buried in San Francisco National Cemetery.

4.

Private Michael Glassley* died on

November 18, 1904 after his discharge, but apparently from some form of illness

originally contracted during his military service.

In 1906, a War Department letter

notifying the then deceased Private Glassley of his award was addressed to him

in “Stevensville, Montana.” He is buried

at Fort Bayard, N.M..

5.

Private Patrick Hussey*. In 1906, a

War Department approval notification letter was sent to Private Hussey in Belt,

Montana, which was his residence in 1898. There is no record of receipt or

return. It was likely not a current

address. Records indicate that

Hussey had re-enlisted in the Coastal Artillery in 1901 but deserted in

September 1901. These enlistment

records, with the desertion entry, should have been available to the War

Department when Private Hussey was included on the January 1906 approved list.

There is no confirmation of his death, although a “Patrick Hussey” died in Minot

North Dakota in 1920.

6.

Private James Harrington.

As noted from the 1906 War Department documentation, all of General

Lawton’s recommendations for the Medal of Honor from the Battle of San Miguel

were approved, except Private Harrington, who was specifically excluded because

he had been killed in the May 16, 1899 at the Battle at San Isidiro. As

discussed above, Private Harrington was particularly cited by General Lawton for

his bravery. Furthermore, Captain

Birkheimer, in a June 3, 1899 after action report on the two battles, stated:

The voices of Young and Private Harrington are hushed in the stillness

of the grave,

yet at this moment I can hear them cheerily urging the scouts on the

attack. Let

their surviving comrades, each and all, receive the award

appropriate to their deeds

of valor. (Emphasis added by author)[15]

This reference to the “surviving comrades”

suggests that Captain Birkheimer may have been aware of the limitation on having

a Medal of Honor awarded to a deceased soldier; hence Private Harrington’s name,

after General Lawton’s death in December 1899, did not follow in the War

Department review and approval with General Lawton’s other recommendations.

Private Harrington is buried in Riverview

Cemetery, Portland, Oregon.

7.

Private J. Killion* was killed on June

9,1899 in a military action near Morong, Philippines. He was buried in Manila.

It seems likely that the War Department was aware of Private Killion’s

death when the approval list was issued in 1906; hence he also never made it

from General Lawton’s 1899 recommendation list into the subsequent War

Department review and approval process.

8.

Private

T.M Sweeney* was killed in another subsequent action in the Philippines at

San Isidiro on October 24, 1900. Like

Private Killion, the War Department was likely aware of his death which is why

he too never made it from General Lawton’s recommendation list to the 1906 War

Department approved list. He is buried in San Francisco National Cemetery.

(While Harrington, Killion and Sweeney can be distinguished

from the first five soldiers on the foregoing list as not having their names on

the final 1906 War Department approval lists, there seems no doubt that the

failure to issue Medals of Honor to these three soldiers was a result of the

“Killed/No Medal” policy.)

9.

Private J. W. McIntyre*, who was on

the January 8,1906 War Department approval list for the Battle of San Isidiro

(and on both of General Lawton’s lists) suffered a particularly egregious form

of injustice. The War Department notification letter was sent to him on January

12, 1906 and addressed to him only at “Fargo, North Dakota.”

It was returned as undelivered and there is no further record of War

Department efforts to locate him. McIntyre

lived until May 26, 1930 when he died in Columbus, N.M.

His pension record reflects that date of death as well as his service

with his unit in the Philippines.[16]

His burial location is unknown.

How the War Department missed the opportunity to find Private McIntyre seems

remarkable.

10.

Corporal William F. Thomas* appears to

be in the same category as Private McIntyre in that he survived the 1906 War

Department award date but did not receive a Medal of Honor.

In a letter dated April 6, 1906, the War Department attempted to

communicate with Thomas regarding his approved award.

That letter was sent to Dickinson, North Dakota (his address of record

from 1898) but returned by an acquaintance with a note that Thomas was likely in

San Francisco. It appears the

letter was then forwarded to San Francisco but there is no confirmation of

receipt. (The great San Francisco

earthquake occurred on April 18, 1906.)

However, in a July 25, 1906 article in the Bismarck, North Dakota

Tribune, William F. Thomas was reported to be in Bismarck (most recently of San

Francisco where his house burned in the earthquake) and headed to a job at a

nearby North Dakota ranch. No death

certificate has been located for Thomas.

11.

Private Simon Harris (who appeared on

both of Lawton’s lists) died on January 22, 1963. He suffered the same injustice

as Private McIntyre as Corporal Thomas, since he also survived his award date.

Like McIntyre, he had a military pension record. Harris also had a VA record.

17 He is buried in Memorial Park Cemetery,

in Kokomo, Indiana. In January

1906, a War Department approval letter was sent to him care of the “Dept of

Police, Manilla”. Prior

correspondence from Private Harris to the Army on April 5, 1902, in which he

inquired about the status of his Medal of Honor, stated that he was then working

for the Manila Police Department. A response to that letter by the War

Department on June 4, 1902 advised Private Harris that he had not received the

Medal of Honor. Obviously, this was inconsistent with the January 8, 1906 War

Department approval notification.

DELAYED

ARMY DECISIONS REGARDING SOLDIERS RECOMMENDED

BY

GENERAL LAWTON

The Medal of Honor recommendation for Captain Birkheimer

resulted in his award on July 15, 1902 for his action at San Miguel.

However, as noted above, not until January 8, 1906 ---after a six-year

delay involving consideration and reconsideration of the soldiers on General

Lawton’s original lists of recommendations --- did the War Department issue the

approved list for the Battle of San Miguel.

The War Department approved list for the Battle of San Isidiro followed

shortly thereafter on April 4, 1906.

The issuance of these approval lists was ultimately

triggered by a request from Senator C. W. Fulton on behalf of then former

Private Edward Lyon. Lyon had

inquired on December 24, 1905 about his Medal of Honor since he was aware of

General Lawton’s recommendation and Captain Birkheimer’s endorsement regarding

Medals of Honor for himself and other soldiers serving in Young’s Scouts.

In contrast to the lack of action between 1899 and Lyon’s letter in

December 1905, the War Department review of Edward Lyon’s inquiry was remarkably

swift since the San Miguel approved list, which included Edward Lyon, was issued

only 15 days later (and over the holidays at that) on January 8, 1906.

Regardless of the reason for this delay from 1899 to

1906---and it was certainly not the fault of any of the recommended

soldiers---this delay had distinct consequences for the soldiers who were

recommended and approved for Medals of Honor but who died prior to 1906.

In fact, if it were not for Edward Lyon’s inquiry, approval lists might

have never been issued by the War Department, and General Lawton’s

recommendations, except the one for Captain Birkheimer, would have never been

addressed.

CONCLUSION

One can reasonably argue that, when in 1918 the War

Department corrected its flawed interpretation of the 1862 Act, it should have

examined Medal of Honor records for discriminations like those identified in the

records of soldiers like Sergeant Fuller and Private Collins, or at least

reviewed the Medal of Honor records of more recent actions such as those found

in the 1906 War Department lists for the Philippine Insurrection---particularly

since a General Order noted the deaths of four soldiers who did receive Medals

of Honor.

Such a review might well have been challenging, but

consider the enormity of the important review that the War Department did in

fact conduct in 1916----when it reviewed all Medal of Honor awards up to that

date, and actually revoked 911 Medals of Honor which were determined not

properly issued, primarily since acts of gallantry were not involved. Would not

a War Department review to identify those soldiers who unfairly received no

Medals of Honor despite approval been just as important---or arguably even more

important?

As the late Senator and Medal of Honor recipient Daniel K.

Inouye remarked in a speech in 2001:

There is no statute of limitations on honor. It’s never too late to do

what is right. A nation

that forgets or fails to honor our heroes is a nation destined for

oblivion.

It is not too late for the thirteen soldiers in this

article. They must not be forgotten.

Medals of Honor need to be issued.

[1] A document entitled Handling

Medal of Honor Cases in the Correspondence and Examining Division, The

Adjutant General’s Office, compiled by C.E. Berlew, December 16, 1912,

Item # 1702191.

[2] Dwight S. Mears, The Medal of

Honor: The Evolution of America’s Highest Military Decoration (Lawrence:

University of Kansas Press, 2008), pp.34-35.

[3] Memorandum, Adjutant General’s

Office, March 25, 1902. This opinion was in response to a request dated

August 1891 from the Adjutant General of Vermont requesting a Medal of

Hoor for Bvt. Major General George J. Stannard, U.S. Volunteers, during

the Civil War. Stannard died on June 1, 1886 and therefore was deceased

at the time of the August 1891 request.

[4] War Department Memorandum dated

February 15, 1918 for the Adjutant General of the Army: Subject:

Posthumous Award of the Medal of Honor.

[6] Captain Rueben Bernard letter of

recommendation to Colonel John S. Sherburne, December 20, 1869, NARA, RG

75. See document at Appendix 2.

[7] See document at Appendix 3.

[8] See document at Appendix 4.

[9] Michael C. Eberhardt, The Battle

of Chiricahua Pass: Medals of Honor Denied October 1869, The Cochise

County Historical Journal, Vol. 50, No. 1, Spring-Summer 2020.

[10] Major General H. W. Lawton, U.S.

Volunteers Commanding. September 26, 1899 Report of an Expedition in the

Provinces of Bulucan, Nueva Ecija, and Pampamga, Luzon, P.I. (San

Isidiro or Northern Expedition), p.92.

[12] War Department Memorandum dated

January 6, 1906, signed by Assistant Secretary of War, Robert Shaw

Oliver. See document at Appendix 5.

[13] War Department Memorandum dated

January 6, 1906 signed by The Military Secretary, Charles J. Bonaparte.

See document at Appendix 6.

[14] War Department Memorandum dated

April 4, 1906 signed by the Acting Secretary of War. See document at

Appendix 7.

[15] War Department Memorandum dated

January 4, 1906, Case of E.E. Lyon, application for the award to him of

a Medal of Honor, Document No. M.S. 1084888 at page 2 citing the

June3,1899 letter from Captain Wm. E. Birkheimer, Captain, 3rd

Artillery, Acting Judge Advocate.

[16] See documents at Appendix 8.

[17] See documents at

Appendix 9.

This article as a printable pdf can be found

here

![]()

![]()